|

Астронет: А. В. Архипов/SETI-XXI Археологическая разведка Луны: результаты проекта SAAM http://www.astronet.ru/db/msg/1177358/e-index.html |

|

Archaeological Reconnaissance of the Moon:

Results of SAAM Project

A.V. Arkhipov

(rai@ira.kharkov.ua)

Institute of Radio Astronomy, Nat. Acad. Sci. of Ukraine

(Материалы конференции "SETI-XXI")

Our Moon is a

potential indicator of a possible alien presence near the Earth at

some time during the past 4 billion years. To ascertain the presence

of alien artifacts, a survey for ruin-like formations on the Moon

has been carried out as a precursor to lunar archaeology. Computer

algorithms for semi-automatic, archaeological photo-reconnaissance

are discussed. About 80,000 Clementine lunar orbital images have

been processed, and a number of quasi-rectangular patterns found.

Morphological analysis of these patterns leads to possible

reconstructions of their evolution in terms of erosion. Two

scenarios are considered: 1) the collapse of subsurface

quasi-rectangular systems of caverns, and 2) the erosion of hills

with quasi-rectangular lattices of lineaments. We also note the

presence of embankment-like, quadrangular, hollow hills with

rectangular depressions nearby. Tectonic (geologic) interpretations

of these features are considered. The similarity of these patterns

to terrestrial archaeological sites and proposed lunar base concepts

suggest the need for further study and future in situ exploration.

1. Introduction

The idea of

lunar archaeology was discussed long before space flight. In the

1930s, J.Wyndham (alias J.Beynon) wrote "The Last Lunarians" - a

fictional report about an archaeological mission to the Moon

[1]. In writing

about the discovery of an ancient lunar artifact in the short story,

The Sentinel

, Arthur C. Clarke

said: "There are times when a scientist must not be afraid to make a

fool of himself" [2]. Today, the

idea of exploring the Moon for non-human artifacts is not a popular

one among selenologists. Yet, because we know so little about the

Moon, the investigation of unusual surface features can only add to

our knowledge. When we return to the Moon, it is possible that lunar

archaeological studies may someday follow.

It has been

argued [3], [4] that the Moon

could be used as an indicator of extraterrestrial visits to our

solar system. Unfortunately, the detection of ET artifacts on the

Moon is outside the interest of most selenologists due to their

orientation towards natural formations and processes. It is also not

of interest to mainstream archaeologists, as archaeology tends to

adhere to a pre-Copernican geocentric point-of-view.

In 1992, the

Search for Alien Artifacts on the Moon (SAAM) - the first

privately-organized archaeological reconnaissance of the Moon - was

initiated. The justifications of lunar SETI, the wording of specific

principles of lunar archaeology, and the search for promising areas

on the Moon were the first stage of the project (1992-95).

Preliminary results of lunar exploration [5] show that the

search for alien artifacts on the Moon is a promising SETI-strategy,

especially in the context of lunar colonization plans. The aim of

the second stage of SAAM (1996-2001) was the search for promising

targets of lunar archaeological study. The goals of this second

stage involved 1) developing new algorithms for space archaeological

reconnaissance, 2) using these algorithms to detect possible

archaeological sites on the Moon, and 3) examining the reaction of

mainstream scientists to these results.

2. Methodology

It is

generally accepted that the search for alien artifacts on the Moon

is not necessary because there are none. Circular logic leads to a

deadlock: no finds, hence no searches, hence no finds, etc. Given

the success in using terrestrial remote sensing to find

archaeological sites on Earth, can similar techniques be used to

find possible artificial constructions on the Moon and other

planets? Hardly, if planetologist think only in terms of natural

formations. For example, the ancient Khorezmian fortress

Koy-Krylgan-kala in Uzbekistan, constructed between the 4th century

BC to the first century AD, appeared as an impact crater before

excavation in 1956 (Fig. 1). On the Moon, Koy-Krylgan-kala would not

be perceived among all of the impact craters.

|

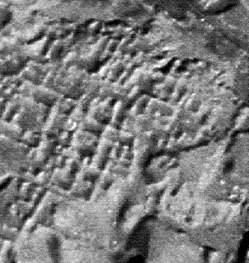

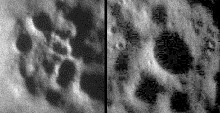

| Fig. 1. The ancient Khorezmian fortress Koy-Krylgan-kala appeared as an impact crater on the air photo (left); its artificiality is obvious after the excavations in 1956 (right) [6]. |

Instead of

the current presumption that all surface features are natural, an

alternative search strategy is to be open to the possible existence

of artifacts. If we are open to this possibility, then one can

extend Carl Sagan's search criteria for detecting signs of life on

Earth [7] to other

planets:

"Let us first imagine a photographic

reconnaissance by orbiter spacecraft of the Earth in reflected

visible light. We imagine we are geologically competent but have no

prior knowledge of the habitability of the Earth. Photography of the

Earth at a range of surface resolutions down to 1 km reveals a great

deal that is of geological and meteorological interest, but nothing

whatever of biological interest. At 1 km resolution, even with very

high contrast, there is no sign of life, intelligent or otherwise,

in Washington, London, Paris, Moscow, or Peking. We have examined

many thousands of photographs of the Earth at this resolution with

negative results. However when the resolution is improved to about

100 m, a few hundred photographs of say 10 km x 10 km coverage are

adequate to uncover terrestrial civilization. The patterns revealed

at 100 m resolution are the agricultural and urban reworking of the

Earth's surface in rectangular

arrays... These patterns would be extremely

difficult to understand on geological grounds even on a highly

faulted planet. Such rectangular arrays are clearly not a

thermodynamic or mechanical equilibrium configuration of a planetary

surface. And it is precisely the departure from thermodynamic

equilibrium which draws our attention to such photographs."

In 1962 Sagan

spoke on the possibility of discovering alien artifacts on the Moon

stating that "Forthcoming photographic reconnaissance of the moon

from space vehicles - particularly of the back - might bear these

possibilities in mind." [8]

Rectangular patterns on air-space photos are recognized as signs of human

culture in the remote sensing of the Earth and air archaeology

[9]. It seems

reasonable then to search for rectangular patterns on the Moon. For

example, assume that the equivalent of proposed modern lunar bases

were built long ago (e.g., 1-4 billion years ago) on the Moon. Such

structures would have been built under the surface for protection

from ionizing radiation and meteorites. Today these ancient

structures might appear as eroded systems of low ridges and

depressions, covered by regolith and craters (Fig. 2).

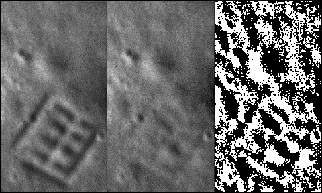

|

| Fig. 2. Simulation of probable HIRES view of ancient settlement on the Moon (left). The erosion wipes off the surface tracks of construction (center), but the SAAM processing could reveal the rectangular anomaly (right). |

A wealth of

lunar imagery collected by the Clementine probe are available in

digital form [10]. Initial

SETI studies [11] used images

from the ultraviolet-visible (UVVIS) camera. The resolution of UVVIS

images is ~200 m. According to Sagan's detection criteria, this

resolution would not be sufficient even to detect the presence of

our own civilization on Earth. Studies of the Moon at this

resolution would probably not reveal any convincing evidence of the

existence of artificial structures. On the other hand, Clementine's

high-resolution (HIRES) camera produced images of adequate

resolution (9-27 m), but they are much more numerous (~ 600,000

images total) and they are thus largely unstudied. The next section

discusses algorithms for automatically scanning large numbers of

HIRES images for potential artifacts.

3. Algorithms

3.1. Preliminary Fractal Test

As a rule,

the structure of natural landscapes is self-similar over a range of

spatial scale. For example, lunar craters between 10-1 m

to 10 4 m in

size appear similar in structure. In contrast to the self-similar

structure of natural features, the structure of artificial objects

is expressed over a narrower range of scale. Hence, possible

artifacts in an image might be recognized as anomalies in the

distribution of spatial detail as a function of scale. The search

for such anomalies is the essence of the fractal method proposed by

M.C. Stein and M.J. Carlotto [12], [13].

Unfortunately their method is too computationally-intensive to

process all of the candidate HIRES images (~80,000).

An

alternative algorithm that is simpler and faster was used for the

same purpose. Let M(r) be the probability distribution of the

distances between local minima in brightness along horizontal lines

in an image. M(r) thus provides a measure of the size distribution

of image detail. At long scales, this function can be approximated

by the fractal power law:

| (1) |

As artificial

objects have some typical size, their presence should increase the

squared residuals of linear regression:

| (2) |

where C is a

constant. According to empirical results, M(r) of the HIRES images

can be approximated by a power law at r > 4 pixels. The regression

is calculated from 4 < r < 31 pixels

(i.e., over a scale range from 50 to 900m).

Images are

divided into K=12, 96x96 pixel regions. In each region the best

model parameters are calculated by least squares, and the average of

the squared residuals determined:

| (3) |

where k is

the number of the test square, gk compensates for gain variations across the sensor, and N is

the number of scales. The average dispersion is estimated from these

regional squared residuals.

An analysis

of 733 HIRES images using the 0.75 micrometer filter, from orbits

112-115 (up to 75 deg. latitude) shows the distribution of residuals

to be Gaussian in form. According to the Student's criterion for

K=12 estimates, if the inequality

| (4) |

is true in

any test square, this area could be considered as statistically

anomalous with a probability of 0.95.

3.2. Detailed Fractal Test

A modified

version of Stein's fractal method was used as a more detailed test.

First, the range of HIRES image brightness was increased linearly up

to 256 gradations. Then the image could be considered as an

intensity surface in a 3-D rectangular frame of coordinates (x and y

are the pixel coordinates, and z the brightness). Stein's method can

be thought of as enclosing the image intensity surface in volume

elements. These volume elements are cubes with a side of 2r, where r

is the scale in terms of pixel coordinates or brightness. Let V(r)

be the average minimal volume of such

elements enclosing an image intensity surface at some point. Then

the surface area is A(r) = V(r)/2r.

As a function of scale, A(r) characterizes the size distribution of

image details. The fractal linear relation between log A(r) and log

r is a good approximation for natural landscapes. However, fractals

do not approximate artificial objects as a rule. This is why Stein

used the average of the squared residuals of the linear regression

| (5) |

as a measure

of artificiality. Unfortunately, the value of the squared residuals

depends on the number of pixels in an image. Therefore, it is

difficult to compare images with different sizes. Moreover, shadows

increase the residuals and generate false alarms. These problems can

be resolved by the non-linear regression:

| (6) |

where the

'artificiality parameter' "alpha" is independent of the

image size.

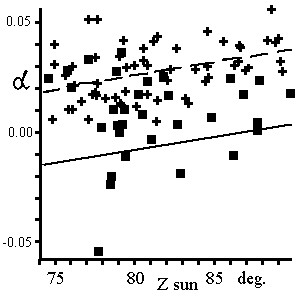

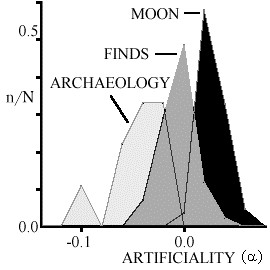

Fig. 3 plots

alpha of a random set of images representing the natural

lunar background (crosses), and the set of images containing

anomalous objects (squares). The shadows lead to values of

alpha greater than zero, but anomalous objects have values

less than zero. At any Solar zenith angle, Zsun the anomalous

formations have systematically lower alpha than the random

set of HIRES images. The average linear regression relating

alpha of the random set and Zsun is shown as a dashed line where the standard deviation of the

crosses from this regression is 0.0113. A deviation of 3 sigma

(solid line) is adopted as a formal criterion for the final

selection of candidate objects.

|

| Fig. 3. Selection of lunar features based on 'artificiality parameter' alpha |

3.3. Rectangle Test

The rectangle

test reveals rectangular patterns of lineaments on the lunar

surface. For each pixel of the image, a second pixel at a distance

of 6 pixels and a given position angle is selected. Let N be the

total number of pixel pairs, and n be the number of pairs where the

pixel brightnesses are equal. The function

| (7) |

characterizes

the anisotropy of the image in terms of position angle. To correct

for camera effects it is normalized by its average over many images.

The anisotropy is smoothed and position angle maxima are found. The

maxima are the orientations of lineament groups. If there are 90

deg. ? 10 deg. differences between maxima, the image is classified

as interesting.

3.4. SAAM Transformation

To aid in

false alarm rejection, the SAAM transformation (Fig. 2) of the image

was used to enhance subtle details of the lunar surface. This

transformation involves smoothing the image over a sliding circular

window of radius R, and subtracting the result from the initial

image. Pixel that are brighter than the smoothed level (difference

greater than zero) are labeled as 'white'; the others are 'black'.

Clipping helps us to see details of both low and high contrast.

Moreover, large details (greater than R in size) are de-emphasized

and so do not interfere with smaller-sized features.

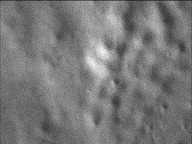

3.5. SCHEME Algorithm

The SCHEME

algorithm searches for local extremities of lunar relief. It does so

by detecting peaks in the image intensity surface in the direction

of the sun. An example of the SCHEME algorithm is shown in Fig. 4.

|

| Fig. 4. The image LHD0331A.062 and a map of relief extremities found by the SCHEME algorithm. |

3.6. Geological Test

J. Fiebag has

suggested that when parallelism exists between a structure and the

lineaments of its surroundings, it is likely to be natural [14]. Although

human activities do sometimes correlate with geological lineaments

(e.g. rivers), the conservative Fiebag test was applied to the lunar

finds.

The lineament

orientation of surroundings was estimated by the rectangle test

technique applied to the ultraviolet-visible (UVVIS) camera. The

UVVIS image covers 196 times the HIRES area with the same 0.75

micrometer filter. Only peaks in the anisotropy (Eq. 7) with

statistical significance of greater than 0.9 were taken into

account. If one of the two directions of the rectangular formation

on a HIRES-image is within 10 deg. of any significant UVVIS

direction, the object is not considered as interesting. This test

rejects about 60% of finds.

4. Finds

4.1. Catalogue

Only the

polar HIRES images of 75 deg. to 90 deg. latitudes were processed in

our survey because of their oblique lighting. The preliminary

fractal, rectangular, geological tests and the SAAM filter were used

with two additional tests:

- Shadow Filter - In order to reduce false alarms

excessively shadowed images were discarded. If more than 5% of

pixels are dimmer than 10% of the maximum brightness amplitude,

that image was ignored. Files of less than 13 KB size were

discarded as well.

- FREX - For filtering of shadow interference

after the preliminary fractal test, the following procedure was

used: The "artificiality parameter" (alpha) was computed as

in Section 3.2 section, but for only 1 of every 5 points to speed

up the analysis of the images. The average linear regression

relating alpha of the random image set and zenith angle

of the Sun was calculated by this simple algorithm. If the value

of alpha for an image was lower than the regression value

minus 1/2 of its standard deviation, the image was selected.

The

preliminary fractal test, shadow filter, FREX and rectangular tests

selected ~5% of the images as interesting. The selected files were

SAAM filtered and tested visually. About 97% of the selections were

ignored after SAAM testing. The remaining 128 finds are catalogued.

Only 47 catalogued images were retained after the geological test.

Their orientations were different by 10 deg. or more from

significant directions of background lineaments. Finally, only 18 of

these 47 images were selected as most interesting by the full

fractal test. Their alpha values deviate from the

regression line for 100 random images by more than 3 standard

deviations.

The images of

highest interest are shown in Table 1. (The full set of images are

listed in Appendix with the images of highest interest shown in

bold.) The finds in the catalogue are described as systems of simple

quasi-rectangular elements: depressions (d), furrows (f), quadrangle hills

(h), rectangular patterns of craterlets (p), and ridges (r). Thus,

an abbreviation such as 'dr' in the last column is a system with

quasi-rectangular depression(s) and quasi-rectangular ridges. This

method of description is convenient for morphological analysis.

|

Table 1. Catalogue of highest interest finds | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Concerning

the lower-ranked images, it is noted that human activity sometimes

correlates with geological lineaments (e.g. valleys, rivers,

deposits around faults, and others) as mentioned earlier. That is

why a negative result of the geological test does not necessarily

indicate a natural object. A positive result would, however, provide

further evidence of artificiality. Similarly, eroded objects could

be of low contrast in orbital imagery. Their fractal properties

might not be significantly different from background, and so a

negative fractal test result could undervalue the find. For these

reasons, all of the finds in Table 1 are of potential interest for

lunar archaeological reconnaissance.

4.2. Morphology

There are two

main types of finds.

Quasi-rectangular patterns of depressions ('wafers')

- About 69% of the

finds are of this type. A wafer is a cluster of rectangular

depressions with rectangular ridges between them. Such a pattern may

be seen in the example in Fig. 5. Presumably, an isolated, single

rectangular depression could be considered an extreme form of this

type. Moreover, there are transitional forms from rectangular

patterns of craterlets to wafers. In Table 1 wafers have

descriptions with d, dr, or p elements. The typical size of a wafer

is 1-3 km. The size of a depression in a wafer is 0.1-2 km.

Quasi-rectangular patterns of depressions occur in smooth terrains,

e.g., between craters, or at the bottom of large-scale craters.

|

| Fig. 5. The example of a wafer find (image LHD5472Q.287). |

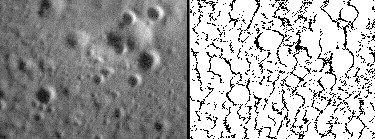

Quasi-rectangular lattices of lineaments ('lattices') -

These comprise about

30% of the finds. A lattice is a complex of interlacing, broken

ridges or furrows, which form a quasi-rectangular pattern (Fig. 6).

This morphological type is present in Table 1 as complexes of r

and/or f elements without d. These lineaments have a typical width

of ~50 m and cover ~1 sq. km. in territory. Lattices occur on slopes

and hill tops, where the regolith layer is thinnest. Apparently,

what we see is subsurface structure rather than some organization of

regolith.

|

| Fig. 6. The SAAM processing reveals the lattice pattern on the HIRES image LHD5165R.171. |

|

| Fig. 7. Hollow quadrangle hills with rectangular depressions around them could be lunar embankments. |

Besides

wafers and lattices, quadrangle hills are worthy of separate

description (Fig. 7). The hills are located in formations of both

morphological types. The dimensions of such hills are 0.3-1 km.

Usually the quadrangle hill has a craterlet on its top. Sometimes

the top depression is so large that the hill appears hollow.

Rectangular depressions around hills are a rarity on the Moon, but

are common for man-made mounds on Earth.

4.3. Interpretations

The possible

evolution of these structures over time can be visualized from the

available images. The reconstruction of wafer evolution is shown in

Fig. 8. The simplest, probably the first stage formation, is a

regular pattern of craterlets (Fig. 8a). Hypothetically, this could

be the result of the collapse or drainage of regolith into

subsurface caverns. Expanding craterlets become angular. Then a

rectangular lattice of ridges appears between them (Fig. 8a,b). The

rectangular lineaments around the formation (Fig. 8c) show a regular

and local structure suggestive of subsurface caverns. A possible

cavern system is seen after its total collapse (Fig. 8d). The bottom

collapses (Fig. 8e) and slope terraces [17] in

rectangular depressions suggest several levels of caves.

|

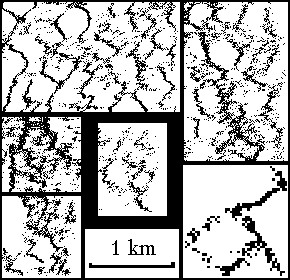

| Fig. 8. Wafer examples in evolutionary order, from left to right: (a) LHD0316A.083, (b) LHD0470B.112, (c) LHD5443Q.291, (d) LHD5472Q.287, and (e) LHD5661R.068. |

|

| Fig. 9. Lattice examples in evolutionary order, from left to right: (a) LHD0558B.072, (b) LHD5559Q.279, (c) LHD6749R.318, and (d) LHD6158R.320. |

The lattice

evolution could be interpreted in terms of erosion as well (Fig. 9).

Apparently, the first (simplest) stage of a lattice is the

quasi-rectangular system of narrow furrows/cracks (Fig. 9a). The

cracks expand (Fig. 9b) and transform into a quasi-rectangular

pattern of ridges (Fig. 9c). Fig. 9d shows a quadrangle mesa-like

hill surrounded by a ridge system (enhanced using a high-pass

filter). Apparently, such ridges are a relatively stable aspect of

the hill they reside on.

Intact

subsurface caverns or very eroded wafers and lattices are almost

invisible in low contrast images. Indeed, some rectangular patterns

are found in the relief-enhanced schemes (Fig. 10). A few elements

are discernable in the original images. For example, the lattice

seen in the bottom-right corner of the scheme in Fig. 4 is just

barely perceivable in the original image.

|

| Fig. 10. Hidden rectangular patterns on the schemes (local extremities of relief) of HIRES images LHD0146A.210, LHD0331A.062, LHD0558B.072, LHD4691Q.253, LHD5243Q.208, and LHD6158R.320. |

|

| Fig. 11. The air view of the Ancient Assyrian ruins of Assur resemble the lunar lattice in Fig. 6. |

These

rectangular systems of depressions and ridges resemble terrestrial

ruins. For example, the patterns in Figures 6 and 10 are similar to

the Ancient Assyrian ruins of Assur [18] (Fig.11).

For

comparison, the detailed fractal test (Section 3.2) is used to

compute the the 'artificiality parameter' (alpha) in Eq. (6)

over the random set of HIRES images (MOON), our finds (FINDS) and a

collection of air-space photos of terrestrial archaeological objects

[19], [20]

(ARCHAEOLOGY). Fig. 12 shows the resultant histograms. It is

possible that alpha values of the lunar finds are shifted

towards the geological background because of the thick regolith

cover. Still, some finds have the same alpha values as

terrestrial archaeological sites.

|

| Fig. 12. The artificiality parameter for the lunar background (MOON), the finds, and terrestrial archaeology. |

Many lunar

geologists explain rectangular depressions on the Moon in terms of

fractures (structural features) at the surface that were present

before the impact events which formed the craters. We have found

compact groups containing rectangular and round depressions of the

same size (Fig. 13). Wafers and lattices appear too localized and

regular in form to be tectonic features or jointing patterns

resulting from multiple impacts. These are reasons to doubt a

geological interpretation for all rectangular formations.

|

| Fig. 13. Argument against the geological fractures: the compact groups of neighbouring rectangular and round depressions of same size (LHD5705R.282 and LHD5814R.295). |

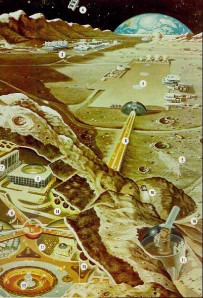

In proposed

lunar base concepts, the rectangular patterns of subsurface

constructions would be visible on the surface [21], [22], [23]. Such

complexes could thus appear as wafer or lattice patterns.

Subsurface, rectangular, multilevel caves are unknown in lunar

geology. However, they are usually considered in modern plans for

lunar bases, as are hollow hills (Fig. 14). Quadrangular and hollow

hills on the Moon are thus worthy of attention as well.

|

| Fig. 14. Modern concept of a lunar base within a hollow hill. Compare with Fig. 7. |

Of course,

some or all of our finds could be geological formations. But the

possibility that they could be archaeological features is so

important that it should not be ignored a priori . Ultimately, only human exploration of the Moon

will determine whether these features are artificial or natural in

origin.

5. Scientific Reaction

The reaction

of mainstream science to this study is perhaps the most interesting

result of our project. There is a paradoxical contradiction between

the vision expressed in science fiction and the agendas of

scientific research. Unfortunately, idea of artificial objects on

the Moon has been discredited by sensational press [24]. As a

result, serious lunar research is not of interest to editors of

scientific journals or even popular science magazines.

As an

experiment, popular reports of our work were submitted to

Archeologia

(France), Sky and

Telescope (USA), and

Spaceflight

(UK). None of them responded. Scientific American (USA) sent inspiring words: "I found your

discussion in the latest META news interesting. Please let me know

how the research progresses in the future... The search for such

artifacts is certainly an important one... As your and other

searches progress, we may want to have an article about the effort."

Not even the hint of interest in extraterrestrial archaeology has

yet appeared in Scientific American .

Correspondence with scientific journals is rather

predictable. For example, the reviewer of the Journal of the British

Interplanetary Society wrote: "The problem with Arkhipov's work is that he has not

tried to explain his features in any way other than in terms of

alien artifacts... Perhaps the author could be persuaded to develop

his technique and write a paper on that rather than its use in

finding ruins on the Moon?" Archaeologists, as a rule, don't

theorize on natural explanations. They explore in situ . To find, we must search. Unfortunately,

planetary geologists have no interest in conducting archaeological

searches. That is why even discussion on archaeological

reconnaissance of the Moon is taboo for the referees.

The reaction

of the SETI community is especially interesting. According to the

director of the SETI Institute, Dr. Seth Shostak, "I think the main

problem with taking serious action in these regards is the lack of

funding and the setting of priorities. This is, alas, always a

problem for SETI as there are still only a rather small number of

researchers involved, and they are presently more disposed to search

for signals than for artifacts." Even followers of E. von Daniken (

Ancient Astronauts

Society and

Archaeology,

Astronautics & SETI Research Association ) ignore the Moon. Although

the SETI League

, Society for Planetary SETI Research

(SPSR), and the

Russian SETI Center

support these

studies, few scientists dare to search for evidence of

extraterrestrial intelligence on the Moon.

Serious

interest in archaeological reconnaissance of the Moon is practically

nonexistent in the planetary science community. Yet, as revealed by

the SAAM project, patterns similar to terrestrial archaeological

sites do exist on the Moon. Hopefully, lunar scientists may someday

be more willing to consider the exciting possibility of non-human

artifacts on the Moon.

6. Conclusions

It is shown

that computerized archaeological reconnaissance of the Moon is

practical. The proposed methods can be used for more extensive lunar

survey, and for planetary SETI in general.

About 80,000

Clementine lunar orbital images have been processed, and a number of

quasi-rectangular patterns were found in accordance with Sagan's

criterion for the detection of intelligent activity in satellite

imagery. The morphological analysis of these finds leads to the

reconstruction of their evolution in terms of erosion. Two possible

evolutionary sequences can be constructed: 1) the collapse of

subsurface quasi-rectangular systems of caverns, and 2) the erosion

of hills with quasi-rectangular lattices of lineaments. In addition,

embankment-like, quadrangle and hollow hills with rectangular

depressions were also observed.

These finds

resemble terrestrial archaeological sites and modern lunar base

concepts. It is recommended that they be explored in situ as possible artifacts.

A catalogue

of promising objects for archaeological reconnaissance of the Moon

has been compiled. Whether they prove to be artificial or not, these

features are examples of unusual lunar geology and merit further

study.

Modern

science and society are not yet prepared for the archaeological

reconnaissance of the Moon. Nevertheless, a discussion on lunar

archaeology will likely occur following the eventual colonization of

our satellite.

Geological

interpretations of lunar relief are well known, but we must take

into consideration other possibilities as well.

Acknowledgements

The author is

very grateful to Dr. Y.G. Shkuratov for access to the Clementine

CDs. I also thank Dr. M.Carlotto, Dr. J.Fiebag, Dr. T.Van Flandern

and Dr. J.Strange for discussions and support.

Appendix: Complete Catalogue of Finds

|

Longitude [25] |

Latitude |

File [26] |

Elements |

|

11.05 |

89.16 |

LHD5814R.295 |

d |

|

13.63 |

85.57 |

LHD5741R.295 |

d |

|

16.08 |

-76.10 |

LHD0480B.030 |

f |

|

20.03 |

-81.24 |

LHD0395A.160 |

p |

|

20.69 |

-79.70 |

LHD0159B.293 |

dr |

|

22.50 |

80.63 |

LHD5686R.160 |

r |

|

25.38 |

75.50 |

LHB5443Q.291 |

prf |

|

28.25 |

-76.50 |

LHD0132B.290 |

dr |

|

28.35 |

79.10 |

LHD5502Q.290 |

f |

|

31.16 |

80.78 |

LHD5833R.157 |

f |

|

31.21 |

78.82 |

LHD5256Q.293 |

d |

|

32.97 |

79.60 |

LHD5538Q.289 |

f |

|

33.55 |

77.27 |

LHD5715Q.156 |

dr |

|

33.57 |

77.05 |

LHD5713Q.156 |

dr |

|

35.45 |

81.20 |

LHD5555R.289 |

rfd |

|

37.00 |

77.58 |

LHD5472Q.287 |

pr |

|

37.18 |

79.86 |

LHD5525Q.287 |

df |

|

41.93 |

-82.88 |

LHD0280A.151 |

fd |

|

43.09 |

86.94 |

LHD5724R.286 |

dr |

|

44.05 |

-75.87 |

LHD0445B.151 |

r |

|

51.34 |

-83.68 |

LHD0233A.147 |

f |

|

53.95 |

-83.54 |

LHD0287A.146 |

rd |

|

56.88 |

87.01 |

LHD5705R.282 |

dr |

|

60.29 |

79.20 |

LHD5559Q.279 |

d |

|

60.30 |

85.14 |

LHD5636R.280 |

p |

|

108.97 |

-76.82 |

LHD0412B.127 |

rhf |

|

109.85 |

-82.38 |

LHD0344A.126 |

d |

|

113.40 |

82.50 |

LHD5350R.260 |

fdr |

|

123.50 |

86.07 |

LHD5652R.126 |

df |

|

124.55 |

-82.47 |

LHD0282A.121 |

d |

|

128.05 |

80.00 |

LHD5375R.254 |

? |

|

128.25 |

-78.26 |

LHD0162B.253 |

f |

|

128.41 |

-76.13 |

LHD0191B.253 |

r |

|

128.83 |

82.91 |

LHD5459R.254 |

dr |

|

130.26 |

-82.91 |

LHD0073A.252 |

d |

|

130.33 |

-82.75 |

LHD0274A.119 |

rp |

|

130.52 |

79.32 |

LHD4691Q.253 |

pf |

|

130.71 |

80.68 |

LHD4722R.253 |

dr |

|

131.20 |

-78.77 |

LHD0111B.252 |

dr |

|

135.66 |

80.05 |

LHD4807R.251 |

? |

|

137.97 |

-84.74 |

LHD0276A.116 |

dr |

|

139.41 |

-86.30 |

LHD0184A.115 |

f |

|

145.91 |

77.84 |

LHD5288Q.247 |

f |

|

148.00 |

-81.36 |

LHD0248A.113 |

f |

|

148.41 |

-79.04 |

LHD0305B.113 |

d |

|

149.69 |

-84.26 |

LHD0231A.112 |

f |

|

150.71 |

-81.43 |

LHD0315A.112 |

rd |

|

151.29 |

-77.99 |

LHD0415B.112 |

d |

|

151.44 |

-76.24 |

LHD0470B.112 |

pr |

|

154.36 |

83.95 |

LHD6979R.244 |

p |

|

155.35 |

83.91 |

LHD5605R.112 |

dp |

|

156.86 |

83.25 |

LHD5564R.243 |

f |

|

159.68 |

-78.18 |

LHD0343B.109 |

pr |

|

164.46 |

76.18 |

LHD4993Q.240 |

rf |

|

164.51 |

81.34 |

LHD5173R.240 |

fd |

|

166.93 |

89.03 |

LHD5643R.114 |

dr |

|

167.15 |

80.91 |

LHD5286R.239 |

f |

|

169.86 |

81.35 |

LHD5175R.238 |

d |

|

169.87 |

79.18 |

LHD5107Q.238 |

dr |

|

171.02 |

-81.44 |

LHD0095A.238 |

p |

|

179.43 |

89.72 |

LHD5696R.248 |

fp |

|

190.15 |

-77.39 |

LHD0469B.098 |

rf |

|

191.53 |

83.32 |

LHD5417R.230 |

pr |

|

191.54 |

83.21 |

LHD5416R.230 |

r |

|

192.67 |

-80.56 |

LHD0308A.097 |

r |

|

192.83 |

-81.40 |

LHD0096A.230 |

dr |

|

192.90 |

-76.89 |

LHD0392B.097 |

f |

|

197.24 |

89.46 |

LHD5611R.108 |

drf |

|

200.20 |

78.82 |

LHD5279Q.227 |

dr |

|

224.67 |

-76.57 |

LHD0421B.085 |

dr |

|

224.72 |

-86.21 |

LHD0175A.083 |

r |

|

229.10 |

-80.45 |

LHD0316A.083 |

p |

|

230.32 |

-83.27 |

LHD0516A.082 |

pd |

|

232.01 |

-76.20 |

LHD0210B.215 |

f |

|

232.08 |

86.83 |

LHD5588R.217 |

fr |

|

242.82 |

87.26 |

LHD5629R.214 |

df |

|

243.37 |

82.05 |

LHD5628R.080 |

dr |

|

244.03 |

-81.12 |

LHD0146A.210 |

d |

|

244.99 |

85.05 |

LHD7605R.344 |

r |

|

246.08 |

81.88 |

LHD7638R.343 |

fh |

|

246.21 |

-82.25 |

LHD0142A.209 |

dr |

|

250.58 |

-85.48 |

LHD0193A.073 |

r |

|

251.14 |

-82.54 |

LHD0140A.207 |

r |

|

251.65 |

79.76 |

LHD5397Q.209 |

f |

|

254.56 |

79.99 |

LHD5250Q.208 |

f |

|

254.65 |

-80.58 |

LHD0148A.206 |

r |

|

258.78 |

-77.45 |

LHD0558B.072 |

f |

|

261.17 |

86.87 |

LHD5466R.208 |

dr |

|

266.18 |

-83.86 |

LHD0278A.068 |

r |

|

266.42 |

86.58 |

LHD5492R.206 |

dr |

|

268.33 |

87.79 |

LHD5595R.207 |

fp |

|

269.63 |

85.11 |

LHD5650R.072 |

d |

|

269.77 |

87.47 |

LHD5521R.206 |

dr |

|

272.70 |

82.72 |

LHD5562R.202 |

r |

|

273.41 |

79.55 |

LHD5545Q.069 |

d |

|

273.56 |

79.74 |

LHD5547Q.069 |

d |

|

281.47 |

-82.36 |

LHD0273A.063 |

fd |

|

284.08 |

87.80 |

LHD5717R.202 |

dr |

|

289.90 |

-80.94 |

LHD0149A.193 |

d |

|

290.49 |

87.58 |

LHD5661R.068 |

d |

|

291.22 |

-75.94 |

LHD0211B.193 |

d |

|

292.29 |

77.16 |

LHD5116Q.194 |

d |

|

292.30 |

77.07 |

LHD5110Q.194 |

d |

|

293.74 |

-80.73 |

LHD0315A.059 |

p |

|

296.28 |

-79.60 |

LHD0173B.191 |

dr |

|

297.82 |

84.15 |

LHD5528R.193 |

dr |

|

300.02 |

79.68 |

LHD5345Q.059 |

hd |

|

300.98 |

80.42 |

LHD5441R.191 |

d |

|

301.21 |

80.96 |

LHD5456R.191 |

dr |

|

301.28 |

85.55 |

LHD6749R.318 |

r |

|

301.55 |

-86.03 |

LHD0082A.320 |

h |

|

301.58 |

-88.19 |

LHD0119A.052 |

r |

|

306.10 |

-77.54 |

LHD0387B.055 |

dr |

|

311.45 |

86.05 |

LHD6158R.320 |

rh |

|

312.61 |

77.97 |

LHD5576Q.054 |

dr |

|

312.73 |

78.18 |

LHD5578Q.054 |

dr |

|

312.75 |

78.38 |

LHD5579Q.054 |

dr |

|

314.96 |

77.38 |

LHD5307Q.053 |

dr |

|

315.05 |

77.60 |

LHD5313Q.053 |

d |

|

315.37 |

77.84 |

LHD5314Q.053 |

d |

|

318.16 |

79.39 |

LHD5862Q.316 |

fdr |

|

320.67 |

79.28 |

LHD5916Q.315 |

dr |

|

323.28 |

86.62 |

LHD5574R.052 |

f |

|

329.05 |

-78.41 |

LHD0362B.047 |

fd |

|

338.05 |

86.90 |

LHD5972R.308 |

d |

|

341.12 |

81.88 |

LHA3621R.307 |

dr |

|

349.97 |

87.33 |

LHD5752R.303 |

pr |

|

351.42 |

85.96 |

LHD5165R.171 |

r |

References

- Wyndham, J.

Wanderers of Time

. London: Coronet

Books, 1973, p. 117-134.

- Clarke, A.C.

The Sentinel

. N.Y.: Berkley

Books, 1983, p. 143.

- Arkhipov, A.V.

" Earth-Moon System as a Collector of Alien Artefacts " , J. Brit. Interplanet. Soc

., 1998, 51, 181-184.

- Arkhipov, A.V., and Graham, F.G.

" Lunar SETI: A Justification " , in The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence

(SETI) in the Optical Spectrum II , ed. S.A. Kingsley & G.A. Lemarchand, SPIE

Proceedings, Vol. 2704, SPIE, Washington, 150-154, 1996.

- Ibid.

- Amalrik A.S.

& Mongait A.L. In

Search for Vanished Civilizations . Moscow: Acad. Sci. of USSR, 1959, p. 128-129

(in Russian).

- Sagan, C. The recognition of

extraterrestrial intelligence, Proc. R. Soc. Lond . B. 1975, 189, p.

143-153.

- Carl Sagan in

1962 on Lunar SETI, Selenology,

1995, 14, No. 1,

p.13.

- Holz, R.K.

" Cultural features imaged and observed from Skylab 4 " , In:

Skylab Explores the

Earth . NASA SP-380.

Washington: NASA, 1977, p.225-242.

- DoD/NASA,

Mission to the Moon, Deep Space Program Science Experiment, Clementine EDR

Image Archive . Vol.

1-88. Planetary Data System & Naval Research Laboratory,

Pasadena, 1995 (CDs).

- Carlotto, M.,

Lunar Mysteries, Quest

for Knowledge , 1997,

1, No. 3, p. 61.

- Carlotto,

M.J. and Stein, M.C., A Method for Searching for Artificial Objects

on Planetary Surfaces, J. Brit. Interplanet. Soc ., 1990, 43, p.

209-216.

- Stein, M.C.,

"Fractal image models and object detection," Proc. Society of Photo-optical Instrumentation

Engineers, Vol 845,

pp 293-300, 1987.

- Fiebag J.

Analyse tektonischer Richtungsmuster auf dem Mars. Kein Hinweise auf

knstliche Strukturen in der sdlichen Cydonia-Region, Astronautik, 1990, Heft 1, 9-13, S. 47-48.

- Coordinates

of the image center.

- DoD/NASA,

Mission to the Moon, Deep Space Program Science Experiment, Clementine EDR

Image Archive . Vol.

1-88. Planetary Data System & Naval Research Laboratory,

Pasadena, 1995 (CDs).

- Arkhipov A.V.

" Earth-Moon System as a Collector of Alien Artefacts " , J. Brit. Interplanet. Soc

., 1998, 51, 181-184.

- Hrouda B.

Der Alter Orient

. Hamburg:

C.Bertelsmann, 1991, S.115.

- Fowler M.J.F.

Examples of Satellite Images in Archaeological Application

(http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/mjff/examples.htm)

- Roney J. Cerro de Trinchera

Archeological Sites, The Aerial Archaeology Newsletter. Vol. 1, No. 1, 1998

(http://www.nmia.com/~jaybird/AANewsletter/RoneyOnTrincheras.html

and She_in_shadow.html)

- Stroup T.L. Lunar Bases of the 20th

Century: What Might Have Been, J. Brit. Interplanet. Soc ., 1995, 48, p.

3-10.

- Matsumoto S.,

Yoshida T., Takagi K., Sirko R.J., Renton M.B., McKee J.W. Lunar

Base System Design, J.

Brit. Interplanet. Soc ., 1995, 48, p.

11-14.

- Sadeh W.Z.

& Criswell M.E. Inflatable Structures for a Lunar Base,

J. Brit. Interplanet.

Soc ., 1995,

48, p. 33-38.

- Childress

D.H. Extraterrestrial

Archaeology .

Kempton: Adventures Unlimited Press, 1999, p. 1-168.

- Coordinates

of the image center.

- DoD/NASA, Mission to the Moon, Deep Space Program Science Experiment, Clementine EDR Image Archive . Vol. 1-88. Planetary Data System & Naval Research Laboratory, Pasadena, 1995 (CDs).